On 31 August 1880 Margaret Tod and Ulisse Cantagalli were married in the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Mary’s, Edinburgh, with Ulisse’s brother Romeo, and Margaret’s brother Robert, as witnesses. His Grace, John Menzies Strain, Archbishop of St. Andrews and Edinburgh, officiated, thereby establishing a permanent bond between the two fine cities of Edinburgh and Florence (SCA).

The Tods of Edinburgh

Margaret’s father was Robert Tod, Mill owner, a partner in Alexander & Robert Tod Ltd., Leith Flour Mills (NAS D76/1056), and a Leith Harbour and Dock Commissioner (NAS SC70/4/298).

The Tod family was an old and respected Edinburgh family of merchants and lawyers. Documents show that in January 1727 Robert Tod, Merchant in Edinburgh, leased land from Edward Jossie of West Pans (NAS RS27/102 f.151), and in 1799, one Robert Tod, Merchant, bought ‘a barn and yeard’ in Leith (NAS SC 39/76). This could have been the precursor of Alexander & Robert Tod Ltd., a successful business with assets that included several prime properties in Leith.

In 1897 the company books registered a nominal capital of £200.000, with preferential and ordinary shares valued at £10 a share: “Margaret Tod, or Cantagalli, of Via Michele de Lando, Florence”, had 2429 shares registered in her name (NAS D76/1056).

In May 1864 Robert Tod feud approximately 26 acres of the Lands of Clermiston from William McFie of Clermiston House, Corstorphine (NAS RS27/2443/60, 65). McFie stipulated that any dwelling house erected on this land must cost a minimum of £1,000 sterling with Coach house, Stables, Lodge, and offices extra. By 1865 Thomas McGuffie, a Glasgow architect, had prepared the plans of Clerwood House (RCHAMS D49981/CN), and building was underway.

This move may well have been precipitated by a traumatic incident that took place in Ratho Villa, the Tod family home in Ratho, near Edinburgh, when Jane Seaton, the children’s nursemaid, was brutally murdered by George Bryce, a local man.

Bryce was courting Isobel Brown, the family cook, until Jane Seaton, convinced that he was not to be trusted, warned her against him. This so enraged Bryce that on the morning of 16 April 1864, having made certain that Mr. Tod had left for his business in Leith, he entered the house, pushing past Brown, who pleaded with him to leave, and ran upstairs to the day nursery where he set upon Jane Seaton, pinned her to the floor, and threatened to kill her. On hearing raised voices, Mrs. Tod seized an umbrella and attacked Bryce, beating him across the hands until he let Seaton go. Then, gripping Bryce by the wrist, she urged her to run for help, but Bryce broke free, pursued Seton, and attacked her with a razor: Seaton died instantly.

Mrs Margaret Tod and her daughter Margaret were witnesses at Bryce’s trial. Mrs. Tod’s statement to the court demonstrated tremendous courage and a total disregard for her own safety. The 11 year old Margaret was described as A very intelligent witness, (NAS AD 14/64/238). George Bryce was hanged on 20th June 1864 before a crowd of 20,000 onlookers, the last person to be publicly hanged in Scotland.

Clerwood

Clerwood House still stands, a spacious mansion set in extensive grounds in Corstorphine, a suburb of Edinburgh. Margaret, or Maggie, as she was known to the family, was brought up here with her brothers Thomas, Robert, George, and sister Anne (NAS SC70/4/296). (Fig. 1)

Margaret was no stranger to her future home for she met Ulisse in Florence in 1878 when she called at his store: she was twenty five years old, and Ulisse was thirty nine.

When Ulisse met Margaret’s family in Edinburgh he was impressed by their affluence and stability and described them as ‘like granite’. In contrast, Ulisse’s Mediterranean enthusiasm for art, poetry, and tradition, must have appealed to this stolid Scottish family, for it seems there was little opposition to the marriage (Conti 1999, 24).

The Cantagallis of Florence

The Cantagalli family can boast an ancient pottery tradition, for they were well known in Impruneta (a town south of Florence) as “furnacers”, and as land and property owners: Conti stresses the furnacer’s superiority to the ordinary potter.

Their name goes back to the 15th Century when it is recorded that Bertolo Antonio Cantagalli, an agent rather than a potter, paid Cristofo, the ‘furnacer’ for small shoes to warm the nuns’ hands. It is not known when the Cantagalli ceramics manufactory was established in Florence, but it was certainly in production by the beginning of the 18th century (ibid, 15).

Ulisse Cantagalli’s grandfather, Lorenzo Cantagalli, died an accidental death in 1835, immediately after the marriage of his 22 year old son Giuseppe to Flavia Franceschi. Giuseppe was reputed to be a wealthy man, and lived comfortably with his wife and their four children, Romeo, Ulysse, Cosina, and Flavia, in a well staffed household of servants.

Ulisse and his siblings enjoyed this privileged lifestyle until 1848 when their father was declared bankrupt and, after a humiliating foreclosure, committed suicide: Ulysse, born 18th June 1839, was nine years old. Life had changed drastically for Guiuseppe’s family, and his widow was obliged to move with her children to a small house next to the pottery on Via Nazionale Romana. Flavia continued to run the family business competently, producing mainly Terracotta, and occasionally some good quality glazed pottery.

On 25th November 1876 the city council agreed that the old name of “Road behind the Cantagalli kiln” should be shortened to “Via Cantagalli” in recognition of the family that owned “the age old kiln for Terracotta” (ibid, 16).

Figli di Giuseppe Cantagalli

In 1878 the manufactory was refounded by Ulisse and Romeo and now traded as “Figli di Giuseppe Cantagalli”. Ulisse would prove to be the most capable of the family, ambitious, artistic, a man of vision, and obsessively intent on rebuilding the family reputation.

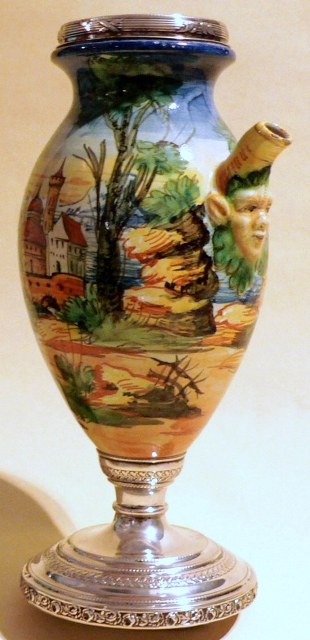

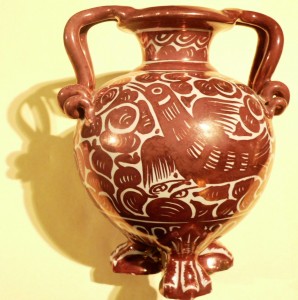

Inspired by the 16th Century maiolica of Deruta, (Fig. 2) Urbino, Castel Durante, Savona and Gubbio, Ulisse set out to emulate the early Renaissance potters, not as fakes, but as reproductions.

Casa Cantagalli was gradually reorganised as an Art establishment, and equipped for the production of maiolica, regarded as the quintessential expression of the Renaissance potter’s art. (Fig. 3)

Luigi Romanelli was pottery manager, or administrator, and the trustworthy Rinaldo Petrucci, who spoke English, accompanied Ulisse on his frequent trips abroad.

For the present, Romeo, who graduated in law from the University of Pisa in 1865, and would later follow a diplomatic career, was the company “Jack of all Trades”.

At this stage in development the manufactory was committed to training skilled painters: with this aim, Ulisse ran a school of Design in the studio of the Painter Marcellin Desboutin where he taught his most talented workers.

He gave full rein to his artisans, who produced work of true artistic merit. A letter to his fiancée on 2nd July 1880 states that his artists were doing so well under his tutelage that he intended to establish a centre of Decorative Art, one that would be a credit to Italy (ibid 17).

In a constant search for new designs, Ulisse scoured the city’s galleries and private collections for models to copy, sketching on large sheets of tissue paper (shiny acetate) using pastel colours which he often enhanced with tempora for better effect. His sketch book demonstrates draughtsmanship, great artistic ability, and a meticulous eye for detail (ibid, 33).

The Artistic Maiolica

The 1870s saw high prices for Italian Maiolica, and Cantagalli produced his first pieces, mainly plates with scenes in the centre and heavily decorated rims, reminiscent of the renaissance style of Urbino. (Fig. 4)

Florence’s Renaissance tradition had attracted the artistically informed of Europe, and the city was now a cultural landmark.

The English influence was so compelling that Florence was styled ‘the Glorious English Florence’, a term supported by major discriminating collectors like Frederick Stibbert, and H.P. Horne, collector and art critic, who both lived in Florence, as well as other men of taste, for example, Lord Carmichael, a passionate collector of Cantagalli, John Ruskin, William Morris, and William De Morgan with whom Ulisse developed a special working relationship.

Casa Cantagalli provided the discerning collectors with high quality, artisan manufactured, copies and reproductions of an earlier era, and with pieces in the Islamic and Moresque styles (ibid, 48). (Fig. 5)

Casa Cantagalli provided the discerning collectors with high quality, artisan manufactured, copies and reproductions of an earlier era, and with pieces in the Islamic and Moresque styles (ibid, 48). (Fig. 5)

He also worked in the “Robbiesque” taste (i.e. Luca Della Robbia, the Renaissance artist), for which Florence was renowned. Casa Cantagalli made the famous Robbiesque style ‘tondi’ (circular sculptures) seen on the Palazzo Pitti’s great stairway. These “Artistic maiolicas” appealed to the market, attracting an international clientele, as did his new, original, models (ibid, 51). (Fig. 6)

Sales were augmented by outlets in strategic points of distribution in Florence and Rome, attracting the custom of foreigners on the Grand Tour.

While other factories were doing less well, the Cantagalli manufactory was thriving, mainly because of the company’s ability to fit into the high culture of the English taste. Maintaining good relationships with British buyers was one of the parts played by Margaret Cantagalli (ibid, 6).

The Cantagalli mark

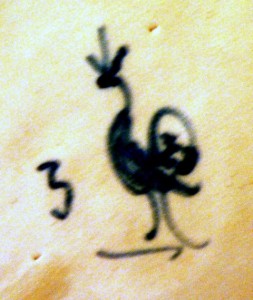

The Cantagalli “singing cockerel”, an idiom of the family name, is similar to that used by other factories, but is smaller, has an open beak and extended neck. One claw is raised, while the other usually rests on a single line. The bird is generally sketchily drawn, (Fig. 7) but can be quite detailed, (Fig. 8) and is usually on the base.

The Cantagalli “singing cockerel”, an idiom of the family name, is similar to that used by other factories, but is smaller, has an open beak and extended neck. One claw is raised, while the other usually rests on a single line. The bird is generally sketchily drawn, (Fig. 7) but can be quite detailed, (Fig. 8) and is usually on the base.

Early pieces also have a shield and family crest, but from 1880 the cockerel is on its own. There is no known reason for added numbers and letters which might signify a model or a painter.

Early pieces also have a shield and family crest, but from 1880 the cockerel is on its own. There is no known reason for added numbers and letters which might signify a model or a painter.

“Firenze Italy” or “Firenze Italia”, sometimes “Italy” or “Italia”, written in blue, is simply the mandatory “Made in Italy” and introduced to comply with the introduction of the, (USA), McKinley Tariff Act of 1890.

Some pieces (1879-80) have a small Florentine lily. Occasional scale or anchor marks have been seen.

Unmarked pieces were possibly made specifically for the family, but the absence of marks could be due to forgery. It is not unusual for the cockerel mark to have been erased in order to pass the piece off as early, and not reproduction (ibid 411-42).

The New Store

The Appendix to Senor Conti’s book gives excerpts, with dates, of Ulisse Cantagalli’s letters to Margaret Tod. These allude mainly to the Casa Cantagalli manufactory: personal passages are excluded. From these we are fortunate to have a contemporary record of Cantagalli’s work from 1778 until his death in 1901: the letters may be referred to, by date, in the appendix (ibid, 121-30).

In 1880 it was decided to build a new Bottega (store). This was to be on a lavish scale as Ulisse planned that it should be in 16th Century Italian tradition, but at the same time had to function as a working pottery.

His letters of 1880 give us some idea of his determination to restore the family reputation, coupled with a need to express his profound passion for modern Arts and Crafts. I will do something magnificent he wrote to his fiancée on 14th May 1880 Wooden and bronze creations, and maybe paintings on glass, are the Arts I want to bring together.

On 17th May he wrote that he was pleased with the progress of the new building which was to be in the style of the Bargello (headquarters of the National Museum of Florence), but more modest. However, having visited Frederick Stibbert’s armoury, he had decided to include that theme also.

By June, under the direction of Professor Gaetano Bianchi the painters were making good progress (Professor Bianchi, the painter who refurbished the Pretorio). As he became aware of the huge scale of his project, Ulisse was inordinately proud of what he had achieved: he now had a spacious showroom magnificently decorated with massive armorial bearings, and arrogant cockerels (the family crest), all set in large panels.

He was particularly satisfied with the splendid vaulted ceiling in the main hall, in the manner of Giotto, and was convinced that, with the new store, he had created a masterpiece.

After extensive refurbishment in the nineteen forties, sadly, none of this splendour survived (ibid, 18).

The Lustre

Ulisse was determined to recreate the subtle finish seen on the lustred pottery from Valencia, Gubbia, and Deruta, a technique said to have been perfected by Maestro Georgio Andreoli of Gubbio at the beginning of the 16th century (Thornton, 2000, 33), although archaeological evidence, as yet to be published, from Orvieto (Marco Mareno Pers Comm), will dispute this. Of Islamic and Spanish origins, the introduction of lustre decoration into Italy made fortunes for the Renaissance factories skilled in the process.

Working from a collection of Renaissance maiolica in the Museo Civico in Pesaro, Terenzio Bertozzini, a furnace master, was the first to recreate Maestro Georgio’s golden and ruby coloured lustre technique. In 1865 he went to work for Conte Giacomo Mattei, a recognised maiolica expert with an interest in experimenting with lustres. Although Ulisse had not perfected the lustre technique, he had made considerable headway, (Fig 9) and in 1880 had a lengthy meeting with Mattei in his Albani workshop in Pesaro.

Working from a collection of Renaissance maiolica in the Museo Civico in Pesaro, Terenzio Bertozzini, a furnace master, was the first to recreate Maestro Georgio’s golden and ruby coloured lustre technique. In 1865 he went to work for Conte Giacomo Mattei, a recognised maiolica expert with an interest in experimenting with lustres. Although Ulisse had not perfected the lustre technique, he had made considerable headway, (Fig 9) and in 1880 had a lengthy meeting with Mattei in his Albani workshop in Pesaro.

He described this visit in a letter to his fiancée on 1st August 1880, and wrote he is going to help me in the technique of copper and ruby lustre on plates. Whatever the outcome of their meeting, it is significant that both workshops, Casa Albani and Casa Cantagalli, were awarded medals at the Milan Exhibition of 1881 for their Arabic-Moresque lustre. (Fig. 10) In 1882 Mattei generously sent Giovanni, Bertozzini’s son, to Florence to help perfect the lustre process (ibid, 38-40).

He described this visit in a letter to his fiancée on 1st August 1880, and wrote he is going to help me in the technique of copper and ruby lustre on plates. Whatever the outcome of their meeting, it is significant that both workshops, Casa Albani and Casa Cantagalli, were awarded medals at the Milan Exhibition of 1881 for their Arabic-Moresque lustre. (Fig. 10) In 1882 Mattei generously sent Giovanni, Bertozzini’s son, to Florence to help perfect the lustre process (ibid, 38-40).

Ulisse was particularly interested in the ruby lustre, and by 1882 he had mastered this, (Figs. 11 & 12) for in October of that year he sold a copy of the ruby lustre Malagan ship bowl to South Kensington Museum (Thornton 2000, 33-40).

Ulisse was particularly interested in the ruby lustre, and by 1882 he had mastered this, (Figs. 11 & 12) for in October of that year he sold a copy of the ruby lustre Malagan ship bowl to South Kensington Museum (Thornton 2000, 33-40).

In 1886 Ulisse took the major decision to build a new kiln as the old one was no longer efficient. To this end he brought in Bridgwood, an expert builder from Stoke in England, and his letters of September 1886 indicate that the kiln was going up satisfactorily, he was happy with Bridgwood’s progress, and they had a good working relationship. By June 1888 the kiln was finished, but poor Bridgwood, who suffered bouts of depression, was in extremely low spirits. The kiln, however, was working perfectly, and Ulisse wrote that he had employed a kilnman from England, name of Salt, at a salary of £170 a year (Conti 1999, 128).

The Exhibitions

The initial success for the company came from major exhibitions, where “Figli de Giuseppe Cantagalli” was plauded by both critics and public, and invariably won a gold medal. It was of vital importance to the company to gauge the market, to become known, and to impress the critics: Ulisse was good at all of this.

The Cantagalli stand occupied a prime position at the 1881 Great Industrial Exhibition in Milan where the maiolica was shown to advantage, and the Arabesque- Moresque designs were well received. Yet another Gold medal was won. Prince Filangieri, founder of the Artistic Museum in Naples was so impressed by the exhibits that he arranged for pieces to be ordered for his Museum.

At the General Italian Exhibition in Turin (1884) the Cantagalli stand was awarded a Gold medal for the quality of the exhibits, and for their reasonable prices: Ulisse was nominated a member of the commission appointed to evaluate exhibits for craftsmanship and imperfections (ibid, 43)

Helen Zimmerman visited this Exhibition and was much taken by the pieces shown by Casa Cantagalli, describing them as cheap and of excellent shape, and commenting. The greatest success is obtained with s in high relief, after the manner of Luca Della Robbia, and vases showing beautiful metallic lustres after the manner of Maestro Georgio. This prismatic glaze is given to it in the muffle furnace by means of salts of copper and silver reduced, or decomposed, in the fumes of green wood, which is the same as the antique process. It is this deoxidation that renders the product expensive’

Helen Zimmerman visited this Exhibition and was much taken by the pieces shown by Casa Cantagalli, describing them as cheap and of excellent shape, and commenting. The greatest success is obtained with s in high relief, after the manner of Luca Della Robbia, and vases showing beautiful metallic lustres after the manner of Maestro Georgio. This prismatic glaze is given to it in the muffle furnace by means of salts of copper and silver reduced, or decomposed, in the fumes of green wood, which is the same as the antique process. It is this deoxidation that renders the product expensive’

She especially admired the successful copies of the pale blue of the old Savona ware (Zimmerman 1897, 214-5). (Figs. 13 & 14)

A Diploma with Honours was presented to Cantagalli at the Universal Exhibition in Antwerp in 1885: this recognised his versatile Maiolica, which included Wall and Floor Tiles, and Fireplaces. The fireplace on show then is presently in the home of Carla Gardini, Ulisse’s nephew (Conti, 1999, 47).

Ulisse designed, and supplied, the flooring for Frederick Sibbert’s castle in Montughli (ibid, 87-9): this commission, coupled with work done in the halls of the Vatican, enhanced his growing reputation (ibid, 74).

Despite failing to receive a single award, Ulisse declared the 1888 Italian Exhibition in London to be an outstanding success (ibid, 47). This exposition lasted for a month, during which time he made several important contacts. His stay in London is enthusiastically detailed in around twenty letters written to his wife between 12th May and 13th June. He tells her of Mr. Fortnum’s visit to the exhibition and his purchase of many pieces, of his meeting with Mr. Armstrong from the South Kensington Museum, and of seeing Mr. William De Morgan.

The highlight of this London visit was an invitation from William Morris to visit him at his home. He describes their lengthy conversations in which they discussed the prices of exhibits, street prices, and the passion of English collectors for his pottery which was in such demand that he had to re-order from the factory in Florence.

Robert Tod visited London the same month, and when the two met, his father-in-law expressed his fondness for Ulisse, and his confidence in the future success of Casa Cantagalli. Soon after this, Robert Tod left for Edinburgh, and Ulisse set off for Stoke where he hoped to visit the English majolica factories. He took time to visit Mrs. Bridgwood, who spoke of her deep gratitude to the Cantagallis for taking care of her husband (according to Cantagalli, the man was losing his mind).

He was still in London on 2nd June, and spent the afternoon at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition with H.P. Horne, where he was introduced to Walter Crane, and wrote there, among other friends of Horne, I got to know Walter Crane. I chatted with them, handled the objects, and discussed them. It was really interesting, full of good taste and originality, demonstrating exuberant artistic movement, and this country’s thirst for research.

This chance meeting proved to be an important contact, for Crane was sufficiently impressed by his work to suggest that it should be used as a model for students at the School of Art and Design.

In 1889 the Exhibition of Artistic Industries at the Artistic Industrial Museum in Rome, and the Paris Exhibition, in celebration of the centenary of the French Revolution, were important events for Casa Cantagalli. The former resulted in a Gold medal, and the latter engendered important business links and contacts, for this is where he met Theodore Deck, Director at Sevres, who would prove to be a good friend.

Other exhibitions followed in Palermo, Brussels, and Turin. Finally, in 1990, came the Universal Exhibition in Paris where the Casa Cantagalli stand, inspired by the Venetian-Gothic, won the commendation of the British Museum (ibid 48).

On his frequent visits to England Ulisse found inspiration in the collections of the British Museum and the South Kensington Museum, where he had access to infinite numbers of photographs of maiolica, very useful to me His friend Charles Drury Edward Fortnum catalogued the early pottery in South Kensington Museum, and sent a copy to Ulisse in Florence which he used for some of his designs.

Fortnum was a major promoter of Casa Cantagalli products, and in 1896 wrote Of reproductions of Urbino wares decorated with grotesques, and some copies of Faenza plates, we have seen none more excellent than those made by Sig. Cantagalli of Florence, and painted by his best artists, (Thornton 2000, 37).

A maiolica plate made for Ulisse’s close friend Drury Fortnum by Casa Cantagalli in 1889 is held in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, and was presented by the factory artists as a measure of their esteem. The plate, painted by Ulderigo Grillanti, depicts the South Kensington catalogue, and is inscribed to their “guide in the art” (Wilson 2003, 6).

Charles Drury Edward Fortnum is considered to be the “second founder” of the Ashmolean Museum. Generally known as Drury Fortnum, he was born in 1820 into a branch of the Piccadilly firm of Fortnum and Mason, and as a young man spent some time in Australia where he gathered natural history specimens.

In 1845 he returned to England, and married, successively, two heiress cousins, thus becoming rich enough to amass his eclectic collection of ceramics, bronzes, finger rings, and glass, which ranged in date from the pre-Classical to his own century.

Closely involved with the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert) from its inception, he acted as their unpaid agent: to have accepted payment, it seems, would have made him a dealer, and not a gentleman. However, clearly disenchanted with the South Kensington Museum’s method of collecting, he made over a large part of his collection to the Ashmolean Museum in the 1880s, and followed this with generous funds to convert the old University building into what we now know as the Ashmolean Museum (ibid, 5).

William De Morgan

A strong relationship developed between Cantagalli and De Morgan, and an important exchange of skills ensued. For health reasons De Morgan had lengthy spells in Florence, and spent much of his time there in the company of his friends, Ulisse and Margaret Cantagalli (Conti 1999, 48).

De Morgan’s wife always denied any commercial connection with Casa Cantagalli, and, resolved to make this absolutely clear, in 1917 she wrote, in part, With regard to the Italian position of the factory, I want to emphasise that there was no sort of connection whatever with the De Morgan work in Italy and the Fabrica Cantagalli. Some time after Signor Cantagalli’s death, my husband got them to paint a vase from his designs, also about four or five dishes, the materials employed being their own. These designs, executed by them for him, were not in any way connected with the output of their own firm, merely an order given to them by him. With regard to the experiment on a paraffin ground, the one successful plate was painted by him himself, and he employed his own men in other attempts of the kind, but merely sent the dishes to be fixed in the Cantagalli kiln – Cantagalli’s people having no more part in the experiment than the Doultons have when a sculptor sends his Terracotta to be fixed (Hamilton 1997, 93).

Although the Cantagalli and De Morgan involvement may not have been of a commercial nature, it is certain that there was a strong intellectual bond between the two men, and despite Evelyn De Morgan’s emphatic denials, probably experiments were discussed and information shared.

In a letter to Margaret, dated 24th May 1888, Ulisse wrote that De Morgan had confided that he had been having failures with lustre pottery over the previous two years, and declared himself ‘ruined’. It is certain that on some of his lengthy visits to Florence, he had some of his pottery fired at Casa Cantagalli. Furthermore, A. Farini, one of Cantagalli’s painters, spent time in De Morgan’s London studio.

In an address to the Society of Arts on “Lustreware” in May 1882, De Morgan stated The best (pieces) I have seen are those of Cantagalli of Florence (ibid, 201).

By 1895 Casa Cantagalli had reached its heyday, and a ministerial survey records that the manufactory employed 121 workers. That year they printed a “descriptive catalogue” of their products with 1069 items, prices and tariffs of 1000 items, and a luxury catalogue with about 60 illustrations which included examples of the several shades of blue seen on almost all the Savona style products. (Fig, 15)

By 1895 Casa Cantagalli had reached its heyday, and a ministerial survey records that the manufactory employed 121 workers. That year they printed a “descriptive catalogue” of their products with 1069 items, prices and tariffs of 1000 items, and a luxury catalogue with about 60 illustrations which included examples of the several shades of blue seen on almost all the Savona style products. (Fig, 15)

Referred to as “pale blue Savona” by Margaret Cantagalli, this was used on a set of dessert plates as a wedding gift to her brother (Conti 1990, 58-9).

In his relentless quest for new designs, (Fig 16) in 1892 Ulisse visited the Azulejos manufactory in Seville, and travelled on from there to Tangier where, he wrote, he placed a large order. His brother Romeo was at this time Italian ambassador to Tangier.

In his relentless quest for new designs, (Fig 16) in 1892 Ulisse visited the Azulejos manufactory in Seville, and travelled on from there to Tangier where, he wrote, he placed a large order. His brother Romeo was at this time Italian ambassador to Tangier.

The trip to Egypt in 1901was made in the hope of finding inspiration for new models and designs, but was not fruitful. Furthermore, this was an extremely arduous one that would prove fatal for Ulisse.

There is an element of presentiment in a letter sent from Cairo on 27th February, for in this Ulisse gave full power to Margaret in deciding the future of the company. Thank you darling for all that you have done for me at the factory. I entrust everything to your decision to which I know that you will always use your good judgment.

On 7th March he again thanked Margaret for all she had done for the factory, adding, I feel that everything goes well. All the news I have received interests me greatly.

When he wrote on 16th March I am better. The doctor says I have had an acute illness. The heart has quietened, and the swelling to the legs has disappeared. I assure you that what I have seen will compensate for the journey it is clear that he had been ill, but seemed to be recovering. Despite this, less than two weeks later, his condition had deteriorated so severely that he no longer had the strength to fight, and on 29th March, he died, with Margaret at his bedside.

Many years later, in 1976, Cantagalli’s daughter Flavia wrote of her father’s last hours. My mother received a call by letter and telegram that prayed for her to join my father who had left for an interesting journey on the Nile. He had already become ill in a hotel in Cairo. We found my father in one of the most luxurious hotels in the city, well cared for. He had lost the strength to tolerate the course of treatment, medical advice, and experiments. I remember only hearing my father saying to my mother, who was seated close by the bed, “Darling I am very tired” Then I did not hear his voice again (ibid, 130-1).

Margaret Tod Cantagalli

Ulisse Cantagalli’s frequent absences from Florence are an indication of the amount of time he spent away from the manufactory: his reliance on Margaret is evident in letters written to her between 1880 and 1901, and confirms Ulisse’s complete trust in her ability to look after the firm’s affairs (ibid, 121-31).

Ulisse Cantagalli’s frequent absences from Florence are an indication of the amount of time he spent away from the manufactory: his reliance on Margaret is evident in letters written to her between 1880 and 1901, and confirms Ulisse’s complete trust in her ability to look after the firm’s affairs (ibid, 121-31).

On his return from London after their official engagement, he wrote to his fiancée on 3rd May about possible new lines for the factory, and detailed a meeting with Theodore Deck, who had shown him the mechanism of several kilns, and given him invaluable practical information.

Acting on his future father-in -law’s advice he had bought a new seven horse power engine. Intriguingly, several letters before their marriage refer to Margaret’s painters working in Florence: Ulisse said he was happy to have them, for they are good men, but the head painter was idle. With his mind teeming with ideas for models in wood, bronze, and on glass, on 14th May 1880 his letter sought Margaret’s opinion of them: he declared that everything went well when he was with her.

Letters on the 11th and 14th June 1880 were full of enthusiastic descriptions of ongoing work in the new Bottego, with the painters working well under the supervision of his friend Professor Gaetano Bianchi. He stressed that it would be magnificent when finished, and although he was certain that his English clients would be impressed, claimed that his sole desire was to make Margaret happy. He recounted his interminable search for inspiration in palaces, churches, galleries, and museums, all in company with Bianchi. Consumed with an ambition to do something absolutely outstanding in life, he asked Aren’t you scared to have a husband devoured by this fire?

Having looked for some time for the right person to manage his business in London, on 9th July 1880 he wrote that he had finally found someone, Mrs. Cashel Hoey, who seemed honest, reliable, and able to present his work as decorative art, not as mechanical perfection: he intended to invite her to be his London representative.

From now on, until the wedding on 30th August, all the letters mentioned work.

His letter of 5th September 1881 was from the Great Industrial Exhibition in Florence, instructing Margaret to write to Luigi and tell him that the last delivery was fine, but, unfortunately, he had dropped, and broken, an amphora.

Between 1881 and 1886 Margaret had three children, Flavia (1881-1979), Lorenzo (1883-1958), and Berta (1886-1972) so perhaps for those years Margaret was able to concentrate her energies on the young Cantagalli family (ibid, 16).

This letter dated 21st May 1888, and sent from the International Exhibition in London, is testament to Ulisse’s confidence in Margaret, and indicates her increasing involvement with the factory.

You joke about the seriousness of your presence and mission in the factory. I, however, believe that you work very well, that you are conscientious, and you being there makes me very happy. You will also be more at ease and be able to give me advice when you have acquired more practical knowledge of the factory.

On 24th May 1888 Ulisse asked Margaret to take care of Mr. Trollope, who would be in Florence the following week to look at garden statuary, and noted that Mrs. Cashel Hoey was writing an article about his catalogue.

A list (one of many) was sent to Margaret on 26th May 1888, detailing models he wanted Luigi to send speedily to London, as June was an important month for the Exhibition. These were intended for the more discriminating collectors and the pieces illustrated in the catalogue would certainly be sought after: he has sent her the Crest of the City of London to be copied.

Two days later, on 28th May, another list was sent to Margaret, again for Luigi’s attention, as the stand was running out of certain models.

Although Ulisse Cantagalli was artistically brilliant, and extremely hard working, he was less conversant with the financial side of the manufactory. His many references to low prices suggest that his main aim was to create art, and to sell it, with scant regard for costs or profit.

In January 1988 he wrote from Rome that the company books showed a loss of 4,000 Lira, and on May 30th, with the benefit of Margaret’s advice, he wrote from London. I have instigated a system of book- keeping as suggested by you and now record all sales, and issue receipts. I would also like to establish costs, but this is more complicated. I was pleased to speak to Senor Luigi as we are now out of Amphora No 7. It sells well and should be made in quantity. However, I can sell dozens of the 4ft. oval Jardinieres with entwining serpents. They will sell for 8/- whereas in Florence this would only be 8 lira. It will also be necessary to stop sending 4 or 5 other models (I have made a list), as I have plenty. Watch that Sr. Luigi has taken note of those that he has sent. I am sorry that you have to tire yourself out going to the factory, seeing to the correspondence, and dealing with other matters.

In August 1895 (no date) Ulisse was perturbed by a letter to Margaret from her father, I do not understand what your father meant by setting up a company in the factory with Romeo. We will have to examine this together before we reply. As I see it, it is intended to give a sum with which we could live independently of the manufactory and this sum would be passed on to the children. In other words, the interest would be assured, but the principal sum could not be touched, and we would only have the use of the interest. We are assured that if we had another child, we could ask for more. I do not understand what your father means by “Let me know about any debts you owe besides the sum to me” You poor darling, you are a millionaire, and I make you suffer so much economy that you find it hard to make ends meet.

We understand from this letter that Robert Tod, a shrewd and wealthy businessman, had already helped out financially, and that Ulisse was unaware of the arrangement between father and daughter.

When Robert Tod died on 9th April 1897 his last Will and Testament, after a few minor bequests to staff and servants, set up a Trust fund for each of his five children, including Margaret, in part, If my daughter, Margaret Tod, now wife of Ulisse Cantagalli of Florence, survive me, her share of the residue of my trust estate shall be paid to herself exclusive of her husband’s rights, but if she predeceases me……and If she is survived by a child or children… my Trustees shall hold the capital for such child or children in equal shares….until attaining twenty four years of age…. And pay to said child or children the yearly interest of their respective shares.

In the unlikely event of Margaret and all the children predeceasing Ulisse Cantagalli, then, and only then, would the income be paid to Ulisse (NAS SC70/4/296).

When he made this Will, Robert Tod was the sole surviving partner of Robert & Alexander Tod Ltd., and owned all the firm’s assets. An Inventory of his personal estate shows that he died an extremely wealthy man with moveable assets of £180,424 sterling (the equivalent of around 10 ½ million pounds sterling today) (NAS SC70/1/357). This did not include Clerwood House, which he bequeathed to his son Thomas.

The Twentieth Century

In 1901 Margaret Cantagalli took over control of the factory with her daughter Flavia, who had studied painting with Eugenio Cecconi and showed considerable artistic talent. Margaret was quite accustomed to her role: after all, she had been involved with the factory since before her marriage.

New ideas were implemented, with a particular emphasis on design: this meant bringing in known artists and painters, and abandoning the copies and reproductions that had been so successful in the past.

The first Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art was held in Turin in 1902 and the Cantagalli display was outstanding, with a large panel of two magnificent Cockerels surrounded by ears of wheat, and a fantastic wall of tiles designed by Cecconi.

This new style embraced by Margaret and Flavia used designs incorporating flora and fauna, poppies, grapes, and pumpkins, and was very reminiscent of Walter Crane’s decorative technique. The popular Art Nouveau form did not entirely appeal to the Cantagallis, but the new models sold, and were included in their catalogue (Conti 1999, 66-7).

A major triumph for Margaret was the important commission to design, and manufacture for, the new headquarters of the Savings Bank of Pistoia. Lavish decoration was employed on ceilings and other areas, while the exterior walls were embellished with a stunning series of plates, similar to medallions. Building was completed in 1905, and in 2005 the Bank published a Centennial edition of the Bank’s history which illustrates the work of Figli di Giuseppe Cantagalli under Margaret’s direction.

The Milan Exhibition of 1906 was a total disaster as fire destroyed most of the stands, including Cantagallis’. Around this time there were signs that the firm was facing a crisis. They now had less than 100 employees, and, most unusually, failed to take part in the 1908 Exhibition.

Although the factory still produced magnificent work, the market was changing, the workers no longer felt the same loyalty to the firm, and new jobs were not difficult to find. Other, more industrialised companies, could produce cheaper goods, and competition was fierce.

By 1910 the workforce was reduced to around 60. Despite mounting problems, in the years preceding the Great War, Casa Cantagalli went ahead and issued a new pattern book with 250 designs, not markedly different from that of twenty years previously (ibid, 72). It is interesting to speculate that the Tod inheritance might have been had something to do with the survival of “Figli di Guiseppe Cantagalli” at this period.

A fickle market, once more favouring the traditional, brought a welcome revival in the company’s fortunes when Casa Cantagalli’s maiolica won the Great Prize in the Turin Exhibition of 1911 for their reproductions. Added to this success, a significant increase in demand for the factory’s production of decorative floor tiles, and for family crests and heraldic devices, was boosted by a successful bid to supply the Florentine Pharmacy with pottery (ibid, 75).

Much heartened by signs of economic recovery after the Great War of 1914-18, and aiming at the expanding post war tourist trade, the firm decided to open a branch in Rome.

The Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Art in Stockholm in 1921 was the first Italian exhibition since the Great War, and of prime importance for the Cantagallis: this is where, reluctantly, they began to accept the new concepts of design that led, soon after, to their collaboration with the designer Guido Balsamo Stella.

The year 1923 was the fiftieth anniversary of Casa Cantagalli and the family marked this occasion by donating fifty Cantagalli pieces to the Museum of Faenza, a small museum in one of the rooms of the factory (ibid, 79).

Margaret Tod’s death in October 1930 saw the decline of the company’s commitment to the traditional. Production was now controlled by Flavia and her husband, Neri Farina Cini, assisted by their Artistic Director, Amerigo Menegatti, the “prolific author of eclectic creations” who proceeded to amass a wide ranging variety of models. An enormous amount of stock soon accumulated in the warehouse and stock rooms, with very little of it marketable. Not surprisingly, the company’s financial position became untenable (ibid).

Frantic rescue attempts were instigated. In order to clear all this surplus stock, it was decided that the best option was to sell through a store in Via Tornabuoi, an area frequented by tourists who might be interested in the traditional Cantagalli style.

A massive advertising campaign began, and this, along with some financial support from Marquises Nicolo and Carlotta Antinori, helped the situation. Teas and light meals were sold in the firm’s garden, adding grist to the mill. Aubrey Adam, a financial adviser, was called in to reorganise the company, and wisely decided to retain the traditional, but also to instigate new systems.

Although Casa Cantagalli rallied sufficiently to win the Great prize at the Monza Exhibition, in less than a year the firm was again floundering. Amerigo Menegatti was brought back as manager, this time with a limited workforce, and proved no more successful than he had previously.

In what was possibly a last resort, in 1936 a contract was signed with the Melamersons (father and son of German origin), owners of a factory in Vietri, to reorganise the Cantagalli manufactory. The firm’s name was changed to “Societa Esecizio Maniffattura Cantagalli”. The Melamersons leased the factory, and although they agreed to continue Cantagalli production, their sole interest was in copying the Cantagalli designs for use in their Vietri based company. The differences with the Melamersons were irreconcilable, and the partnership was terminated.

Between 1936 and 1939, Guido Gambone moved to Florence from Salerno, and worked in the Cantagalli factory where he produced a series of novelties, small figures, donkeys, etc., signing some of his work with a tiny fish.

Many attempts were made by Casa Cantagalli to negotiate with other manufacturers, but it was the end of 1940 before a contract was finally signed with Giuseppe Baduel from the “Italian Consortium of Artistic Maiolicas” in Deruta, in a last attempt to reorganise the company: with the ceramic industry on the decline, this was all too late (ibid, 82-4).

The final years

After the second World War, the firm’s assessment showed a disastrous loss of 3.5 million lira (old lira), and Baduel Cini, financial advisor, and Farina Cini, company president, were forced to resign.

However, when the company was re-evaluated in 1951, the books showed a positive budgetary balance, and in October 1952, Dr. Giorgio Biagiotti took over the lease, and ran the factory until 31st January 1954, at which point it was taken over by SCOMAF (Societa Cooperative Operaia Maioliche Artistiche Fiorerentini) under the direction of Renato Pierattoni with Farini Cini as manager, and a total staff of fifty employees. This venture was committed to reintroducing the traditional designs.

When the Cantagalli premises were sold to a builder in 1962, SCOMAF moved to Sesto, but the Casa Cantagalli administration stayed on in Via Sinese until the factory samples, sketches, designs, brushes, and plans, which constitute il “Fondo Cantagalli” (The Cantagalli archive) could be removed.

Ulisse’s wonderful Bottega was demolished in 1966, and in 1970 around 150 pieces from the sample book, including some rarities, were sold by Sotheby’s Auction House.

The Bargello Museum accepted gifts of examples from Flavia Cini’s house, and other pieces were personally selected by Professor Liverani for the Museum of Faenza.

In 1974 the San Savino Exhibition prompted Luciano Berti to acquire il “Fondo Cantagalli” on behalf of the Museum Internationale delle Ceramiche in Faenza, a gesture in appreciation of the traditional style of Figli de Giuseppe Cantagalli.

Although they survived the intervening years, SCOMAF declared bankruptcy in 1987, and an auction of stock and equipment was held in Firenze on 9th November that year (ibid, 85).

The international reputation established by Casa Cantagalli survives today, with examples to be found far from Florence. In 1897 Cantagalli supplied a collection of his models for the Powerhouse Museum in Sidney, Australia (ibid, 50). Tiffany of New York visited the Bottega in Florence in 1888 and placed an order for their store (ibid, 128). The British Museum holds a collection, as does the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (ibid, 121-130). Glasgow Museum bought 15 examples in 1899. Edinburgh Museum purchased very few, but were most fortunate in 1983 to have several pieces donated by Mr. A.K. Gallie, a great nephew of Margaret Tod and Ulisse Cantagalli, and other donors (Curnow 1992, 108).

My modest collection of Cantagalli maiolica stems from my interest in the rather unlikely union between a Scottish lass, Maggie Tod from Edinburgh, and Cantagalli, the Italian potter from Florence. How did this transpire? And how did it end? I was intrigued to discover the story of a remarkable woman, entirely devoted to an adoring husband, and to his work as an artist. Reading between the lines, we may surmise that her application, together with the Tod wealth, were positive factors in the survival of the Cantagalli manufactory in troubled times.

Fig. 17 Margaret Tod Cantagalli, by kind permission of Signora Cristina Dazzi.

It seems that Margaret did not abandon her roots entirely, for she did visit Clerwood on occasion, and brought her friend, Violet Paget (Vernon Lee, writer), who also lived in Florence. On August 15th 1887 Violet wrote from “Kirnan, The Scores, St. Andrews” I also remark, judging from the stations & on the Forth ferry steamer, that all Scotchwomen have by no means the figure and complexion of Mme Cantagalli & Alice Callander; I never saw such a scrubby, raw visaged lot. I am grateful to Signora Cristina Dazzi for this excerpt of Violet’s letter to her mother.

********

Acknowledgments

My thanks are due to Mr. Roy Gallie, great grand nephew of Ulisse and Margaret Cantagalli, for his photograph of the Tod family tree, and for his introduction to Signora Cristina Dazzi. As Cantagalli family archivist, and the wife of Flavia Cantagalli’s grandson, she has been generous with family information and photographs: I am truly in her debt

I wish to thank Andrew Nicol, curator of Scottish Catholic Archives, who gave me a photocopy of the Cantagalli marriage entry from the marriage register of St. Mary’s Cathedral. Ian Stewart of RCHMS unearthed copies of the original plans of Clerwood House, and I thank him for his interest and help. The City of Edinburgh Council permitted publication of the drawing of Clerwood house, and I am therefore grateful to City archivist Richard Hunter. Thanks also to Rose Watban of the National Museums Scotland, who kindly allowed access to the museum’s Cantagalli collection. I am grateful also to Sarah Tolley who first introduced me to Clerwood, and who shares my interest in Cantagalli. As ever, I am indebted to the staff of NAS for their informed and patient help.

Thank you to Andrea Bertocca, who painstakingly translated the text of Giovanni Conti’s book, and to my husband Ian who, with the utmost patience, translated Ulisse’s letters when he could have been playing the bagpipes.

I am especially indebted to my good friend George Haggarty who interrupted his incredibly busy schedule to photograph all the Cantagalli pieces illustrated here.

REFERENCES

Published Sources

Conti, G 1990 La Maiolica Cantagalli e Le Manifature Ceramiche Fiorentine. Roma.

Curnow, C 1992 Italian Pottery in the national Museums of Scotland. Edinburgh.

Hamilton, M 1997 Rare Spirit – a life of William De Morgan 1839-1917. London.

Thornton, D 2000 ‘Lustred Pottery from the Cantagalli Workshop’ APOLLO-Feb (2000), 33-40.

Wilson, T H 2003 ‘Maiolica Italian Renaissance ceramics in the Ashmolean Museum’, Oxford.

Zimmerman, H 1897 ‘Modern Italian Ceramics’ Magazine of Art (1896-7), 214-15.

Unpublished Sources

RCHAMS: Royal Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments Scotland.

NAS: National Archives of Scotland.

SCA: Scottish Catholic Archives: Register of Marriages.

Sheila Forbes has asserted and given notice of her right under section 77 of the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act of 1988, to be identified as the author of the foregoing article.

You have some good points here. I would really like to argue..I mean discuss them more with you 😉 It not easy what we do (thinking of awesome content) but if you are the same as me then you definitely do this because the work is it’s own reward.

did you ever see a “robbiana” by cantagalli (cm 35×35) with an angel with open whigs and a “cartiglio” in the hands?